The Trunajaya Rebellion (or Trunajaya War , also spelled Trunojoyo Rebellion ) was a rebellion carried out by the Madurese nobleman , Raden Trunajaya , and his ally, troops from Makassar , against the Mataram Sultanate assisted by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in Java in the 1670s. , and ended with the victory of Mataram and the VOC.

This war began with the victory of the rebels: Trunajaya’s troops defeated the royal troops at Gegodog (1676), then succeeded in occupying almost the entire north coast of Java and capturing the Mataram palace at the Plered Palace (1677). King Amangkurat I died while running away from the palace. He was succeeded by his son, Amangkurat IIwho asked the VOC for help and promised payment in money and territory. The involvement of the VOC managed to turn the situation around. VOC and Mataram troops recaptured the occupied Mataram area, and captured Trunajaya’s capital at Kediri (1678). The rebellion continued until Trunajaya was captured by the VOC in late 1679, as well as the defeat, death or surrender of other rebel leaders (1679–1680). Trunajaya became a prisoner of the VOC, but was killed by Amangkurat II during the king’s visit in 1680.

Besides Trunajaya and his allies, Amangkurat II also faced other attempts to usurp the throne of Mataram after his father’s death. His most serious rival was his younger brother, Prince Puger (later Pakubuwana I ) who captured the Plered Palace after being abandoned by Trunajaya’s troops in 1677 and only surrendered in 1681.

|

|||||||

| Parties involved | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Counter claimant to the Mataram throne (after 1677) |

|||||||

| Characters and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|||||||

Background

Amangkurat I ascended the throne of Mataram in 1646, succeeding Sultan Agung , who had expanded Mataram’s territory to include most of Central and East Java, as well as several overseas vassals in southern Sumatra and Kalimantan. [8] The early years of Amangkurat’s reign were marked by the executions and massacres of his political enemies. In response to the failed coup attempt of his brother Prince Alit, he ordered the massacre of clerics he believed were involved in Alit’s rebellion. [9] Alit himself was killed in the failed coup. [9]In 1659 Amangkurat suspected Prince Pekik, his father-in-law and son of the defeated Duke of Surabaya who lived in the Mataram court after Surabaya’s defeat , of leading a conspiracy threatening his life. [10] He ordered to kill Pekik and his relatives. [10] The massacre of East Java’s most important nobility created a rift between Amangkurat and his East Javanese subjects and led to conflict with his son, the crown prince (later Amangkurat II ), who was also Pekik’s grandson. [10] Over the next few years, Amangkurat carried out a number of other murders of members of the nobility who had lost his trust. [10]

Raden Trunajaya (also spelled Trunojoyo) is a descendant of the Madurese rulers, who was forced to live in the Mataram court after the defeat and annexation by Mataram in 1624. [11] After his father was executed by Amangkurat I in 1656, he left the palace, moved to Kajoran, and married the princess from Raden Kajoran , the head of the ruling family there. [12] [11] The Kajoran family is an ancient clerical family and is married to the royal family. [12] Raden Kajoran was concerned about the brutality of Amangkurat I’s reign, including the execution of nobles in the palace. [11]In 1670, Kajoran introduced his son-in-law Trunajaya to the crown prince, who had just been expelled by the king because of a scandal, and the two forged a friendship that included a mutual dislike of Amangkurat. [11] In 1671 Trunajaya returned to Madura, where he used the support of the crown prince to defeat the local governor and become ruler of Madura. [13]

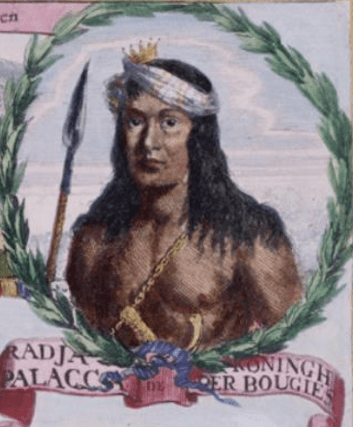

Makassar was a major trading center east of Java. [13] After the VOC’s 1669 victory over the Sultanate of Gowa in the Makassar War , a group of Makassarese soldiers left Makassar to seek their fortune elsewhere. [13] Initially, they settled in the territory of the Sultanate of Banten , but in 1674 they were expelled, and turned to piracy, raiding coastal cities in Java and Nusa Tenggara . [13] The crown prince of Mataram then allowed them to settle in Demung , a village in Tapal Kuda, East Java . [13]In 1675 an additional group of Makassarese fighters and pirates arrived in Demung led by Karaeng Galesong . [13] These wandering Makassar warriors later joined the rebellion as Trunajaya’s allies. [12]

Troops involved

Lacking a permanent army, most of Mataram’s troops were drawn from the army built by the king’s vassals, who also provided weapons and supplies. [14] [15] The majority of these soldiers were farmers who were required by the local authorities ( Javanese : sikep dalem ). [15] In addition, the army included a small number of professional soldiers drawn from the palace guards. [14] These soldiers used cannons , small firearms including sundut rifles ( Javanese : rifles , from Dutch snaphaens ) and carbines ,cavalry , and forts . [16] Historian MC Ricklefs says the transfer of European military technology to the Javanese was “quite urgent”, with gunpowder and weapons made in Java by at least 1620. [15] Europeans were hired to train Javanese army troops in weapons handling, military leadership skills , and construction engineering. [15] Despite this training, however, conscripted peasants of the Javanese army often lacked discipline and fled during battle. [17] [18] Mataram’s army was “much larger” than the 9,000 rebels at Gegodog in September 1676, [1]fell to just a “little company” after the fall of the capital in June 1677, [19] and increased to over 13,000 as it moved towards Trunajaya’s capital of Kediri in late 1678. [2]

The VOC had its own professional army. [15] Each VOC soldier had a sword, small arms, bullets, carrying pouches and belts, smoke bombs, and grenades. [15] The majority of the VOC’s permanent soldiers were Indonesian, with a small number of European soldiers and marines, all under the command of European officers. [20] While in a technological sense, VOC troops were not superior to their indigenous counterparts, [16] they were generally better trained, disciplined, and equipped than indigenous Indonesian soldiers. [15] The VOC troops also differed in logistics: their troops moved step by step followed by long caravans of wagons carrying supplies. [16]This gave them an advantage over the Javanese troops, who often survived by gathering or stealing food while traveling through the countryside and often faced shortages of supplies. [16] The VOC army numbered 1,500 in 1676, [21] but was later added by the Bugis allies under the leadership of Arung Palakka . The first convoy of 1,500 Bugis arrived in Java in late 1678, [5] and by 1679 there were 6,000 Bugis soldiers in Java. [6]

Similar to other wars, Trunajaya’s army and its allies also used cannons, cavalry, and forts. [16] When the VOC captured Surabaya from Trunajaya in May 1677, Trunajaya fled with his twenty bronze cannons, leaving behind 69 iron and 34 bronze guns. [22] Trunajaya’s troops consisted of Javanese, Madurese and Makassarese. [1] When the rebels invaded Java in 1676, they numbered 9,000 [1] and consisted of followers of Trunajaya and fighters of Makassar. Later, the rebellion was followed by other Javanese and Madurese nobles. In particular, the ruler of Giri, one of the most prominent Islamic spiritual rulers in Java, joined in early 1676.[23] Trunajaya’s father-in-law, Raden Kajoran , head of the influential Kajoran family, joined after Trunajaya’s victory at Gegodog in September 1676, [24] and Trunajaya’s uncle, Pangeran Sampang (later Cakraningrat II ) joined after the fall of the capital Mataram in June 1677 . [25]

Military campaign

Beginnings and early rebel victories

The rebellion began with a series of attacks by Makassar pirates based in Demung against trading towns on the north coast of Java. [26] The first attack took place in 1674 in Gresik but was repulsed. [26] Trunajaya entered into a pact and marriage alliance with Karaeng Galesong, the leader of the Makassarese, in 1675 and planned further attacks. In the same year, Makassar-Madurese pirates captured and burned the main cities in northeastern Java, from Pajarakan to Surabaya and Gresik. [26] In view of the failure of the loyalist forces against the rebels, King Amangkurat I appointed a military governor inJepara , the provincial capital on the north coast, and fortified the city. [26] The Mataram forces moving at Demung were defeated, and joint action by Mataram and VOC ships on the coast controlled by pirates was not always successful. [26] Karaeng Galesong moved to Madura, territory of his ally, Trunajaya. In 1676 Trunajaya bestowed upon himself the title Panembahan (Ruler) of Maduretna and received the support of sunan (spiritual ruler) Giri, near Gresik. The attack by the VOC fleet then destroyed the pirate base in Demung, but they did not take action against Trunajaya in Madura. [27]

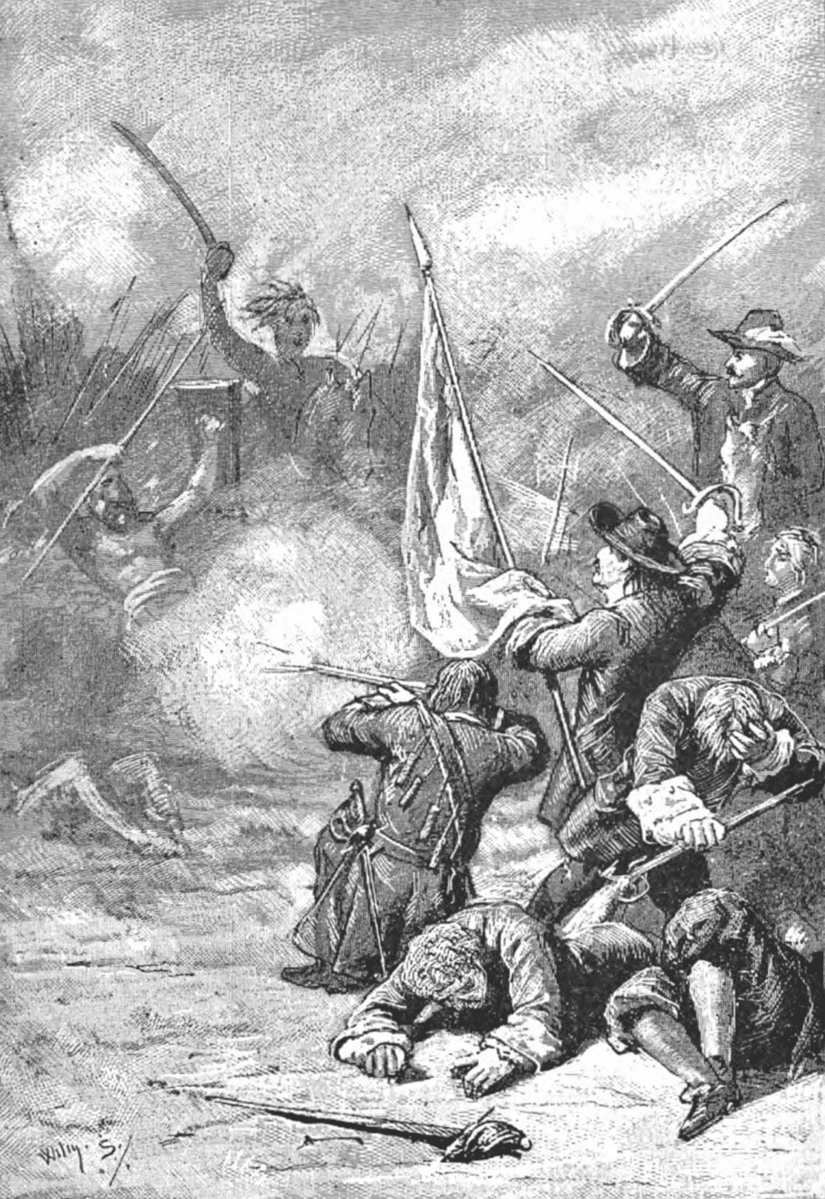

Gegodog Battle

In September 1676, a 9,000-strong rebel army [1] led by Karaeng Galesong crossed from Madura to Java and then captured Surabaya, the main city of East Java. [28] Mataram sent a large army, commanded by the crown prince (later Amangkurat II to meet the rebels. [28] A battle took place at Gegodog, east of Tuban , in 1676, resulting in the total defeat of the much larger Mataram army. [28] ] [29] Loyalist troops were deployed, the king’s uncle, Pangeran Purbaya was killed, and the crown prince fled to Mataram. [28]The crown prince was blamed for this defeat for his long hesitation before attacking the rebels. [28] In addition, there were rumors that he colluded with enemies, including his former vassal Trunajaya. [28] Within months of the victory at Gegodog, the rebels quickly captured trading cities in northern Java, from Surabaya to the west in Cirebon , including the cities of Kudus and Demak . [28] The cities fell easily, partly because their forts had been destroyed due to their conquest by the Sultan Agung of Mataram some 50 years earlier. [28]Only Jepara managed to hold off the attack, as the combined efforts of the new military governor and the new VOC troops strengthened the city just in time. [28] The rebellion spread to the interior when Raden Kajoran, Trunajaya’s influential father-in-law based east of the capital Mataram, joined the rebellion. [24] Kajoran and Trunajaya’s troops marched towards the capital, but were repulsed by loyalist forces. [24]

VOC intervention and fall of the capital Mataram

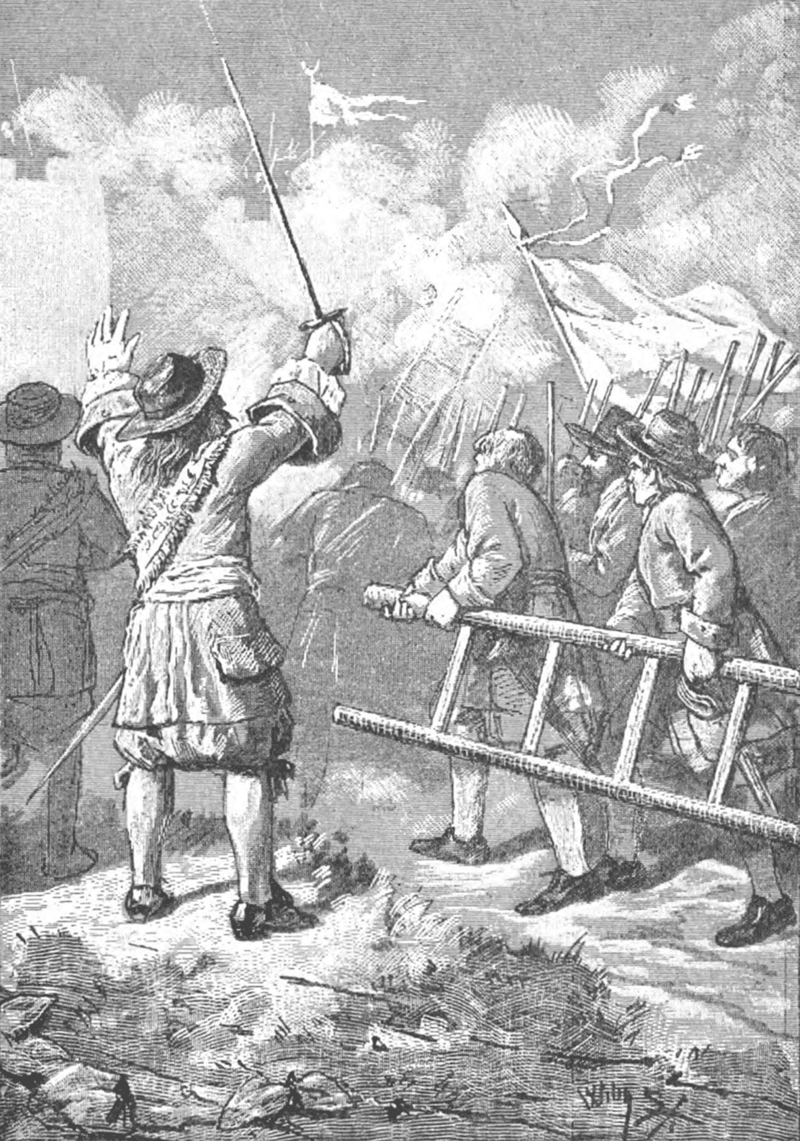

Battle of Surabaya

In response to requests for intervention by Mataram, the VOC sent a large fleet containing Indonesian and European troops, commanded by Admiral Cornelis Speelman . [24] In April 1677 the fleet sailed to Surabaya, where Trunajaya was based. [24] After negotiations failed, Speelman’s troops invaded Surabaya and captured it after heavy fighting. [30] The troops continued to clear the rebels from the area around Surabaya. [30] VOC troops also captured Madura, Trunajaya’s home island, and destroyed his residence there. [31] Trunajaya fled to Surabaya and founded his capital at Kediri. [30]

The fall of Plered

Although the rebels were defeated in Surabaya, the rebel forces campaigning in the interior of Central and East Java were more successful. The rebel military campaign culminated in the fall of the capital Plered in June 1677. [31] The king was ill, and distrust among the royal princes prevented a well-planned resistance. [31] The king fled west with the crown prince and his retinue, allowing the rebels to enter and plunder the capital with little resistance. [31] The rebels then retreated to Kediri, taking the royal treasures with them. [32]

The throne of Amangkurat II and alliance with the VOC

King Amangkurat I died during his retreat in Tegal in July 1677. [31] [21] The crown prince succeeded his father and took the title Amangkurat II, and was accepted by the Javanese nobility in Tegal (his grandmother’s hometown) as well as by the VOC. [33] [21] However, he failed to establish his rule in the nearby city, Cirebon, whose rulers decided to declare independence from Mataram with the support of the Sultanate of Banten . [33] Subsequently, his younger brother Pangeran Puger (later Pakubuwana I) captured the now-destroyed capital, refused to join as Amangkurat II loyalists, and declared himself king with the title Ingalanga Mataram.. [33]

Having no army and wealth and unable to establish his power, Amangkurat decided to ally with the VOC. [34] At this time, Admiral Speelman was in Jepara, sailing there from Surabaya after hearing of the fall of the capital. [33] His troops had recaptured important coastal cities in Central Java, including Semarang , Demak, Kudus, and Pati . [35] Amangkurat moved to Jepara on a VOC ship in September 1677. The king had to agree to the extensive concessions demanded by the VOC in exchange for restoring his monarchy. [34] He promised the VOC revenue from all port cities on the north coast. [34] HighlandsPriangan and Semarang will be handed over to the VOC. [32] The king also agreed to recognize the jurisdiction of the VOC over all non-Javanese living in his territory. [34] Dutch historian HJ de Graaf comments that by doing this, the VOC, as a corporation, engaged in “dangerous speculation”, which they hoped would pay off in the future when their partner would regain control of Mataram. [34]

The VOC–Mataram troops made sluggish progress against the rebels. [32] [34] In early 1678 their control was limited to a few towns on the north-central coast. In 1678, Speelman became Director General of the VOC, replacing Rijcklof van Goens , who became Governor-General (Speelman later became Governor-General in 1681). [32] Command in Jepara was handed over to Anthonio Hurdt , who arrived in June 1678. [32]

The victory of loyalists and the death of Trunajaya

VOC and Mataram troops marched inland against Kediri in September 1678. At the king’s suggestion, the troops were split into three ranks, with no direct route, with the aim of covering more locations and impressing those who hesitated to take sides. [36] The king’s idea worked, and as the military campaign continued, local groups joined the army, desperate for booty. [20] Kediri was captured on 25 November by an assault force led by Captain François Tack . [20] [32] The victorious army continued on to Surabaya, the largest city in East Java, where Amangkurat founded his palace. [37]Elsewhere, the rebels were also defeated. In September 1679, a combined VOC, Javanese and Bugis forces under Sindu Reja and Jan Albert Sloot defeated Raden Kajoran in a battle at Mlambang, near Pajang. [7] [38] Kajoran surrenders but is executed on Sloot’s orders. [38] In November, the VOC and allied Bugis forces under Arung Palakka destroyed the Makassar rebel stronghold at Keper , East Java. [7] In April 1680, after what the VOC viewed as a fierce battle in the war, the rebellious ruler of Giri was defeated and most of his family executed. [7]As the VOC and Amangkurat won more victories, more and more Javanese people declared their loyalty to the king. [7]

After his stronghold fell in Kediri, Trunajaya managed to escape to the mountains of east Java. [39] VOC troops and the king pursued Trunajaya, who, isolated and short of food, surrendered to the VOC in late 1679. [40] [7] Initially, he was treated with respect as a prisoner of the VOC commander. However, during a ceremonial visit to a nobleman’s residence in Payak, East Java, on 2 January 1680, [40] he was stabbed by Amangkurat himself, and the king’s courtiers finished him off. [40] [7] The king defended the killing of a VOC prisoner by saying that Trunajaya had tried to kill him. [41] The VOC was not convinced by this explanation, but chose not to punish the king.[42] A romantic account of Trunajaya’s death appears in the18th century Central Javanese chronicle . [39]

End of the rebellion of Prince Puger

In addition to Trunajaya’s troops, Amangkurat II continued to face opposition from his brother Pangeran Puger, who had captured the old capital at Plered and had seized the throne for himself in 1677. [33] Prior to Trunajaya’s defeat, Amangkurat’s forces had taken no action against him. [34] After Trunajaya was defeated, Amangkurat still could not convince his brother to surrender. [7] In September 1680, Amangkurat built a new capital city at Kartasura . [7] In November, Amangkurat and VOC troops expelled Puger from Plered. [7] However, Puger quickly rebuilt his army, captured Plered again in August 1681, and nearly captured Kartasura. [7]In November 1681, VOC and Mataram troops again defeated Puger, and this time he surrendered and was pardoned by his brother. [7] [43]

end

Amangkurat II secured his reign with the defeat of the rebels. Due to the rebels’ capture and subsequent destruction of the capital at Plered, he built a new capital, Kartasura, in the Pajang district, and moved his court there. [43] A VOC fort was built in the capital, next to the royal residence, to defend it against invasion. [43] As for the VOC, its involvement allowed the cornered and nearly defeated Amangkurat II to remain on his throne. [44] This set a precedent for the VOC supporting Javanese kings and claimants in exchange for concessions. [44]By 1680, however, this policy required high levels of spending to maintain a military presence in Central and East Java, and this led to a decline in VOC finances. [44] The payments promised by Amangkurat were not kept, and by 1682 the king’s debt to the VOC exceeded 1.5 million rials , about five times the amount of the royal estate. [45] The handover of Semarang was delayed due to disputes, [45] and other provisions of the contract were largely ignored by local Javanese officials. [46] Subsequently, an anti-VOC faction developed in the Mataram court, and a member of this faction, Nerangkusuma, became patih (main minister) from 1682 to 1686. [47][46] The poor relationship between Mataram and the VOC continued with the protection of Surapati , an enemy of the VOC, in 1684, [48] and the death of the VOC captain, François Tack at the Mataram court in 1686. [48]

The king’s younger brother, Pangeran Puger, who tried to usurp the throne during the Trunajaya rebellion, was pardoned by the king. [43] However, after the king’s death in 1703 and his son Amangkurat III succeeded , Puger took the throne again. [49] Puger’s claim was supported by the VOC, and the VOC-Puger alliance won the subsequent First Javanese War of Succession (1704–1708). [49] Puger ascended the throne with the title Pakubuwana I and Amangkurat III was exiled to Sri Lanka . [49]

Reference

footnote

- ^ Jump to:a b c d e f Andaya 1981, p. 214–215.

- ^ Jump to:a b Ricklefs 1993, p. 50.

- ^ Ricklefs 1993 , p. 35.

- ^ Jump to:a b Ricklefs 1993, p. 51.

- ^ Jump to:a b Andaya 1981, p. 218.

- ^ Jump to:a b Andaya 1981, p. 221.

- ^ Jump to:a b c d e f g h i j k l Ricklefs 2008, p. 94.

- ^ Pigeaud 1976 , p. 56–57.

- ^ Jump to:a b Pigeaud 1976, p. 55.

- ^ Jump to:a b c d Pigeaud 1976, p. 66.

- ^ Jump to:a b c d Pigeaud 1976, p. 67.

- ^ Jump to:a b c Ricklefs 2008, p. 90.

- ^ Jump to:a b c d e f Pigeaud 1976, p. 68.

- ^ Jump to:a b Houben & Kolff 1988, p. 183.

- ^ Jump to:a b c d e f g Taylor 2012, p. 49.

- ^ Jump to:a b c d e Houben & Kolff 1988, p. 184.

- ^ Houben & Kolff 1988 , p. 183–184.

- ^ Taylor 2012 , p. 49–50.

- ^ Pigeaud 1976 , p. 74.

- ^ Jump to:a b c Pigeaud 1976, p. 79.

- ^ Jump to:a b c Ricklefs 2008, p. 92.

- ^ Ricklefs 1993 , p. 39.

- ^ Ricklefs 1993 , p. 40.

- ^ Jump to:a b c d e Pigeaud 1976, p. 71.

- ^ Ricklefs 1993 , p. 41.

- ^ Jump to:a b c d e Pigeaud 1976, p. 69.

- ^ Pigeaud 1976 , p. 69–70.

- ^ Jump to:a b c d e f g h i Pigeaud 1976, p. 70.

- ^ Andaya 1981 , p. 215.

- ^ Jump to:a b c Pigeaud 1976, p. 72.

- ^ Jump to:a b c d e Pigeaud 1976, p. 73.

- ^ Jump to:a b c d e f Ricklefs 2008, p. 93.

- ^ Jump to:a b c d e Pigeaud 1976, p. 76.

- ^ Jump to:a b c d e f g Pigeaud 1976, p. 77.

- ^ Pigeaud 1976 , p. 76–77.

- ^ Pigeaud 1976 , p. 78-79.

- ^ Pigeaud 1976 , p. 80.

- ^ Jump to:a b Pigeaud 1976, p. 89.

- ^ Jump to:a b Pigeaud 1976, p. 82.

- ^ Jump to:a b c Pigeaud 1976, p. 83.

- ^ Pigeaud 1976 , p. 84.

- ^ Pigeaud 1976 , p. 83–84.

- ^ Jump to:a b c d Pigeaud 1976, p. 94.

- ^ Jump to:a b c Ricklefs 2008, p. 95.

- ^ Jump to:a b Ricklefs 2008, p. 99.

- ^ Jump to:a b Pigeaud 1976, p. 95.

- ^ Ricklefs 2008 , p. 100.

- ^ Jump to:a b Ricklefs 2008, p. 101.

- ^ Jump to:a b c Pigeaud 1976, p. 103.

References

- Andaya, Leonard Y. (1981). The Heritage of Whitewater Palakka: A History of South Sulawesi (Celebes) in the Seventeenth Century . The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. doi : 10.1163/9789004287228 . ISBN 9789004287228 .

- Houben, VJH; Kolff, DHA (1988). “Between Empire Building and State Formation. Official Elites in Java and Mughal India”. Itinerary . 12 (1): 165–194. doi : 10.1017/S016511530002341X .

- Ricklefs, MC (1993). War, Culture and Economy in Java, 1677-1726: Asian and European Imperialism in the Early Kartasura Period . Sydney: Asian Studies Association of Australia. ISBN 978-1-86373-380-9 .

- Ricklefs, MC (2008-09-11). A History of Modern Indonesia Since C.1200 . Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-05201-8 .

- Pigeaud, Theodore Gauthier Thomas (1976). Islamic States in Java 1500–1700: Eight Dutch Books and Articles by Dr HJ de Graaf . The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 90-247-1876-7 .

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (2012). Global Indonesia . Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-95306-1 .